Teresa Reviews “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd” (2000)

Teresa reviews “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd” (2000) and found the changes too hard to swallow.

Fidelity to text: 2 daggers

![]() The overall arc remains but oh, my God! Losing minor characters is understandable but adding a murder and completely rewriting the ending is not.

The overall arc remains but oh, my God! Losing minor characters is understandable but adding a murder and completely rewriting the ending is not.

Quality of movie on its own: 2 daggers

![]() The ending was ridiculous, characters did things for no reason other than because the plot said so. But the scenery, settings, and costumes look great.

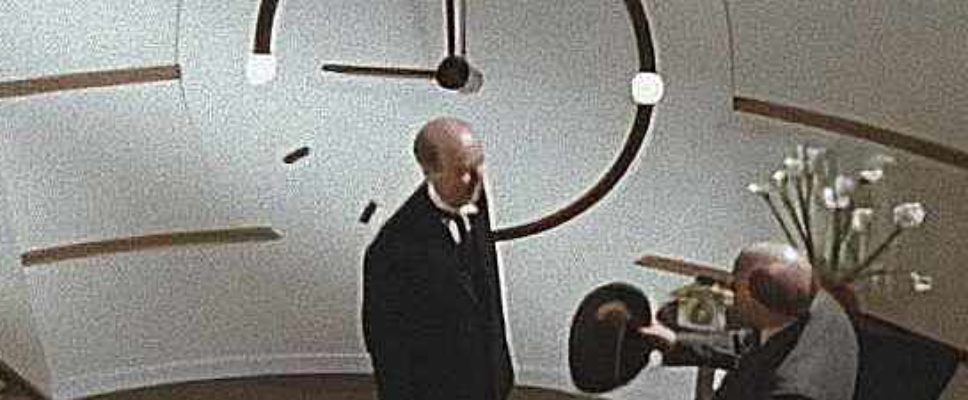

The ending was ridiculous, characters did things for no reason other than because the plot said so. But the scenery, settings, and costumes look great.

Read more of Teresa’s Agatha Christie movie reviews at Peschel Press.

Also, follow Teresa’s discussion of these movies on her podcast.

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was always going to be a tough novel to film. It made Agatha’s reputation and still stuns readers today. When Dear Daughter read Roger for our annotation project, looking for items that needed an explanatory footnote, she screamed when she read the ending. She’d been completely fooled, just like Agatha intended. She ranted for days about how she’d been bamboozled and how, when she went back to the text for clarification, she saw how she’d swallowed every red herring and overlooked the real clues.

So many people have read Roger these days and so many mysteries have been written since its publication that it’s hard to grasp how earth-shattering it was. These days, an unreliable narrator is as common as zucchinis in summer. But in 1926? Not so much.

How do you film a novel that depends on you, dear reader, believing everything the narrator (Dr. Shepherd) tells you? A novel that is told in the first person? We only know what Dr. Shepherd tells us. He’s genuinely puzzled by some of the events surrounding Roger Ackroyd’s murder. He knows that some witnesses are lying, but he doesn’t know why. He never lies. He’s Hercule Poirot’s sidekick in the investigation and so must be trustworthy.

But dear Dr. Shepherd is far more than he seems.

The filmmakers had a choice. They could run with the text, knowing that most of the audience already knew whodunnit. Or, they could rewrite the story for the few viewers who — like Dear Daughter — had not read the book and so would not rage at the TV when a classic mystery got tossed into a chemical vat, altering the very structure of its DNA.

The production company’s other issue was the time gap. The last Poirot was Dumb Witness, aired in 1996. By the time funding returned, four years had passed. Audiences needed to be reintroduced to Poirot as — gasp! — they might have moved on to watching other must-see TV and they needed an explanation for the gap.

Roger Ackroyd filled both needs. It was a blockbuster novel that everyone had heard of and it began with Poirot’s retirement to King’s Abbot to grow vegetable marrows.

So far, so good.

Unfortunately, the producers chose option two. They did not trust Agatha’s text nor did they trust the audience. They went with the safe choice of removing Dr. Shepherd’s first-person narration and having Poirot provide it. They added Chief Inspector Japp to a story that did not need him, thus negating the local constables. Worse, Japp took Dr. Shepherd’s place. Adding Japp meant Dr. Shepherd got relegated to just another potential suspect instead of acting as Poirot’s righthand man, substituting for Hastings somewhere out in Argentina.

It’s vital to the story that Dr. Shepherd be Poirot’s sidekick. Poirot trusts him. Poirot’s trust makes the ending all the more striking.

Diminishing Dr. Shepherd meant downsizing another major character: his sister, Caroline.

Caroline Shepherd was a proto-Miss Marple. She’s a spinster, runs his household, provides him with village gossip, is an acute observer of human nature, and is fascinated by Poirot and by the murder. Caroline also has a strong moral code, something that proves vital to the ending.

She’s mostly gone, popping up only when the plot demands her presence. Her character is so rewritten that she becomes someone else. Thus, when she drives her brother to the meeting at Ackroyd’s chemical factory where Poirot is going to reveal the murder, she waits outside in the car (at Poirot’s request) and conveniently discovers Dr. Shepherd’s journal and his old service revolver in the glove compartment. She reads the journal, is horrified, and then takes it and the journal inside to her brother.

What? Why does she need the revolver? And why is there a gun in a story that had none?

You may not recall a chemical factory in the novel, either. That was another addition since some producer decided the script needed a climactic chase scene. The Kempton Waterworks and Steam Museum provides wonderful eye-candy in early scenes with Roger, his secretary, Geoffrey Raymond, and Roger’s ne’er-do-well adopted son, Ralph Paton. It looks exactly like the kind of dark, satanic mill William Blake railed against. Dr. Shepherd disapproves of it too.

Naturally, the production company wanted to use the factory as much as possible. Thus, we get the completely rewritten ending that tossed every remaining shred of the novel into one of those giant chemical vats. Poirot has everyone assemble in Ackroyd’s office and lectures the suspects. He then states that Chief Inspector Japp will be arresting the suspect … the next day!

What? Japp’s not going to do that. Scotland Yard doesn’t give suspects a head-start to leave the country and flee justice. They arrest the suspect on the spot. I have no idea why this piece of drivel was filmed. It would never happen.

The other suspects file out of the room but Dr. Shepherd remains to verbally spar with Poirot. Caroline comes charging in and shows him the contents of her bag, containing his journal and his revolver.

Why does she do this? Does she want him to shoot Poirot and Japp? Does she want him to shoot himself in front of witnesses? Or does she want him to take hostages so he can flee the country? We are given no reason other than she’s his sister.

Meaningful glances don’t mean a thing when you know nothing about that person or their motivation.

Dr. Shepherd delivers his villain’s monologue (bwa-ha-ha-ha!), seizes the revolver from Caroline’s bag, flees the room, and shoots at Poirot and Japp as they follow. He flees into the chemical factory, presumably filled with workers and volatile chemicals (although we don’t see them).

Poirot and Japp follow and Caroline is once again disappeared. Japp counts shots, knowing that Dr. Shepherd will run out of bullets. He’s a lousy shot, somehow not only missing Poirot and Japp every time, but also managing to miss any of the unlucky workers and the huge vats of highly explosive chemicals that should never be mixed. It’s a wonder that factory didn’t blow up and kill them all and put the audience out of its misery.

Then it’s back to the beginning. Poirot is back at his bank, putting away Dr. Shepherd’s journal and telling us that the countryside is just as steeped in murder as the city. What? Considering how many murders Poirot solved in quaint country villages, this observation shows growing vegetable marrows must have turned his brain into squash. Worse, he tells us that the case will be marked unsolved as a favor to his friend.

Um, no. We know Dr. Shepherd did it. We’ve got his journal telling us and we’ve got him admitting his crimes to Poirot, Japp, and his sister, all of whom are unimpeachable witnesses. And how will they explain Shepherd’s death? An industrial accident?

The film is a great-looking mess and maybe that’s enough for you. It wasn’t for me.

Read more of Teresa’s Agatha Christie movie reviews at Peschel Press.