Book Review: A People’s Guide to Publishing

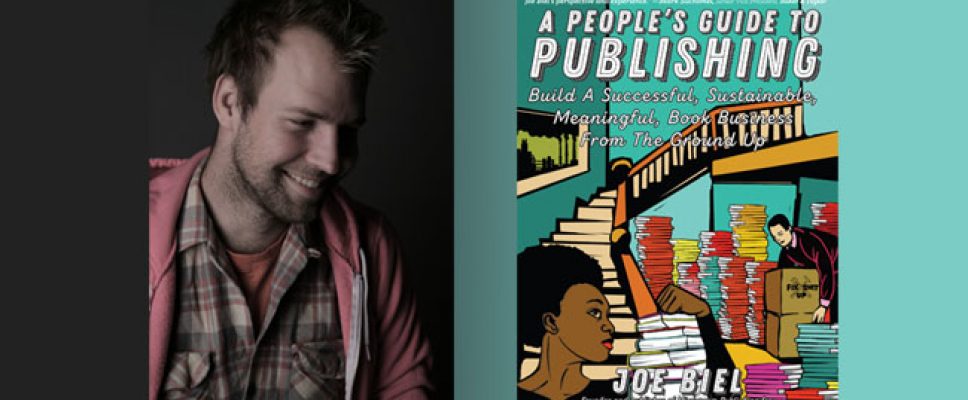

A People’s Guide to Publishing: Build a Successful, Sustainable, Meaningful, Book Business From the Ground Up by Joe Biel

Buy the book from Microcosm Publishing (they make more money this way): Direct Link

To learn more about Joe Biel and Microcosm Publishing (they have a very esoteric line of books you won’t find elsewhere): Official Website

Do not be put off by the typo in the book’s title (!) on the cover (!!) and other typos and grammatical errors sprinkled about. There were enough for me to notice but I’ve seen far, far worse examples from much bigger publishers.

I refer to the unnecessary comma inserted between “Meaningful” and “Book.” It’s very difficult to make an error-free book; even when, as Joe Biel has, you’ve published plenty of them.

Joe Biel owns Microcosm Publishing. He’s been a successful publisher for over twenty years. So despite the typos, A People’s Guide to Publishing is a readable and amusing guide to the business, packed with information and anecdotes about publishing books and publishers.

One reason it took me a long time to read it is because I read it aloud to my long-suffering husband over breakfast. When I wasn’t reading it out loud, I was underlining portions for the benefit of our minuscule publishing house. I learned a lot. (No submissions, please. We’re not there yet. If we’ll ever be, dear. Bill.)

Because of Biel, I better understand why traditional publishers make the ridiculous decisions they do, why their books take a year between acceptance and published; and why they have cash-flow issues. It’s the structure of the business, it’s the U.S. tax code, and it’s the money.

Publishers are all about acquiring properties from authors (aka annoying but talented cattle) that they think will sell. No publisher who plans on staying in business wants to buy a manuscript that loses money. If the manuscript looks like it will sell (an “if” the size of an iceberg), then Publisher assigns it to marketers, designers, and editors to massage the manuscript into the correct size, layout, and appearance to match good-selling competitors already in bookstores.

Notice that the marketing comes first. Again, I repeat: If Publisher doesn’t think the book will sell, Publisher will throw it back onto the stack with all the other rejected manuscripts. It doesn’t matter in the slightest if the manuscript becomes a massive worldwide bestseller. That’s a great big if that rarely comes true. Although, as J.K. Rowling will attest, sometimes it does.

One subject Biel goes into that was new to me was the concept of comps, short for comparisons. The industry uses comps to determine if your manuscript will sell. Publisher looks over the marketplace and identifies desires waiting to be filled and what’s selling. Next, Publisher studies the manuscript, seeing if it fills a hole in the catalog. If you’ve ever wondered why publishers seem to work in unison, this is one of the reasons.

For example: Publisher decides that if cats solving mysteries sell, then ferrets solving mysteries might, too. Why would Publisher go out on this speculative limb? Publisher has noticed that cats solving mysteries don’t sell as well as they used to. Conclusion: The buying public is moving to something new. Publisher wants to fill this need, but without risk.

So Publisher prints one-tenth as many copies of the new title as usual because the population of ferret lovers who read mysteries about ferrets is assumed to be ten percent of the size of the population of cat lovers who read mysteries. Then, Publisher cuts another fifty percent off the initial print run because Publisher isn’t even sure if ferret lovers as a group know how to read.

If you think that there seems to be a lot of guesswork involved in Publisher’s decision-making process, you win a gold star.

If Publisher guesses right, the money rolls in. If Publisher guesses wrong, the money flows out. That upgrade to a larger yacht will have to wait another quarter.

Publishers have to make these decisions for every manuscript. Does this book fit into what we already publish? Is there already demand for this type of book? Will this book sell forever or will the fad vanish overnight? Can the marketing people drum up enough interest before ordering the print run so we have an idea how many copies we’ll actually sell? Are we at a similar price, size, and look to what’s already out there? Will the book be different enough to stand out but not different enough to discourage bookshop owners, reviewers, library buyers, and readers?

Then there is the whole issue of printing the book. Specialty manufacturers print books. They have a language of their own that Publisher has to learn in order to receive books that meet Publisher’s vision at a cost Publisher is willing to pay. Printers have long waiting times because their presses run continuously. Publisher has to negotiate over size and number of books and then get a slot in Printer’s schedule. Economies of scale mean that Publisher pays a lower price per book (sometimes much lower) for 10,000 copies than for 1,000 copies but 10,000 books take up a lot of warehouse space. Space that has to be paid for. Publisher may not be able to sell all 10,000 copies.

In fact, Publisher rarely does. This leads to the amazing concept of returns. Bookshop Owner takes a chance on Publisher’s new line of ferrets solving mysteries solely because Bookshop Owner knows that she can return the unsold copies for up to a year. No questions asked. Full refund. Publisher gets back thousands of unsold ferrets solving mysteries, and they stack up in the warehouse by the pallet load. Decisions have to be made. Remainder them and hope to make back at least the cost of the printing? Or pulp them, thus saving the warehouse fees.

Details like these rarely enter the mind of a writer, yet for Publisher, they are paramount. Or they should be if Publisher wants to stay in business.

So why should you, Writer, care? Because knowing how publishing works can explain the paltry advances or marketing choices or covers that match top-sellers down to the font spelling out the author’s name or why your 250,000-word manuscript had to be cut down to 100,000 words despite how it mangled the story. It’s also why Publisher won’t buy your Dark Ages Highlander/Zombie romance even though you love writing them. Dark Ages Highlander/Zombie romances don’t sell enough for Publisher to recoup their costs.

It’s not personal. It’s just business, as a famous businessman in the movies once said.

Knowing how publishing operates benefits traditionally published authors, and it matters even more for indie writers. If you self-publish, you are a publisher. You are responsible for editing, covers, layout and formatting, pricing, and marketing. Those are all publishing jobs. Cash-flow is as important to you as it is to one of the big publishing houses. If you aren’t making money, you either subsidize your expensive writing hobby with someone else’s money or you quit. Reading A People’s Guide to Publishing will give you a much better understanding of the choices you’ll make along the way.

So let’s talk about why I didn’t give five stars to this wonderful book that every writer (and serious reader) should read. Joe Biel, Microcosm’s publisher, doesn’t like indie authors. He confuses indie writing with vanity presses which will print anything if they’re paid. He believes that writers (despite being annoying but talented cattle) need publishers like him to help fulfill their destinies.

Well. Publishing is his business, and he is not going to encourage writers to go it alone. He wouldn’t remain in business if all of his writers went indie. He could find new ones, because not every writer wants to be their own publisher. Good publishers do plenty of work for their authors, freeing up their time for creative writing. Not every author is cut out to run a business.

Joe Biel also has a serious issue with print on demand. Print on demand is a more expensive way of producing trade paperbacks than having a printer using an offset press. However, print-on-demand means you, indie author, only have to store a few books at a time for events. You don’t have to purchase 10,000 copies to get the lowest possible price per copy. You also don’t have to store those books. You don’t have to do fulfillment with bookstores across the country. With print-on-demand, every book ordered is a book that is sold.

If you are an indie author, print-on-demand is the way to go. You pay for only the copies you need to hand-sell at events. You do not have to warehouse books. You do not have to do fulfillment. You do not make as much money per copy sold either. It’s a trade-off.

My other issue is that A People’s Guide to Publishing does not have an index. Yes, the table of contents is detailed and, yes, the book is well laid-out with plenty of subheads. Nice charts and illustrations, too. But to be most useful, a book like this Needs. An. Index.

Maybe Biel’s comps for A People’s Guide to Publishing didn’t have one or perhaps, he didn’t think the cost of indexing — a professional subspecialty that publishers contract out — was worth it when he figured out how much the Guide would cost to produce versus how much it would earn.

He was wrong. But Joe Biel is right on so many other topics about publishing.

I highly recommend A People’s Guide to Publishing for writers, traditional and indie, and readers interested in the publishing business. If you want to start a publishing house because of the sad lack of ferrets-solving-mysteries, you need this book, badly. It might save you from bankruptcy. At least you’ll understand what you’re getting into before you start throwing money at those ferrets.